Thank you to everyone who joined our Risk appetite in action: Turning boundaries into better decisions, reporting and governance webinar. With a record number of registrations and attendees, it was one of our most engaged sessions to date, and this was reflected in the quality of the questions asked.

The discussion confirmed something we hear consistently from boards, executives and risk teams: risk appetite only creates value when it is usable. When boundaries are clear, measurable and visible, they support faster decisions, stronger escalation and more confident governance. When they are not, they create friction, ambiguity and delay.

We’ve captured and expanded on your questions below. Some have been edited slightly for clarity, but the intent and substance remain unchanged.

If you weren’t able to attend, or would like to revisit the session, the full webinar recording is available to watch on demand:

Q&A topics.

Aggregation/cascading of risk appetite

1. Is there a recommended method for linking BU risks with the enterprise risk appetite?

2. Is it common to have different risk appetite for different areas, such as cyber security, AI, data privacy?

3. Where an organisation might have 3 levels in a risk taxonomy, how do you demonstrate cascading down and across it?

Risk appetite implementation

4. Would you be able to provide examples of risk appetite articulation for risk culture?

5. How do we make risk appetite that can be applicable for both the operational and strategic risks?

6. What are your thoughts on using an enterprise risk matrix to drive appetite?

7. When setting KRIs and their tolerances, should you look to include the upside of the ‘traditional target’ and set equivalent ‘green to amber’ and ‘amber to red’ tolerances to have oversight of overperformance?

8. Any tips on how to quantify the chance of loss?

9. What is the interplay between the residual risk rating which is measured based on consequence and likelihood and a difference scale to the board appetite rating of very low to high?

10. Do you see risk appetite evolving toward dynamic, data-driven models rather than static annual statements? What does that look like in practice?

11. Should there be separate risk appetites for objectives and strategy?

Compliance and risk appetite

Definitions

13. What is the difference between risk appetite and risk tolerance?

Decision-making, strategy and risk appetite

14. Should the decision to proceed with an opportunity be decided by the existing risk appetite? Or should the risk appetite be made flexible by the opportunities decided by the business/ management?

15. Should risk appetite be revised every year in line with the organisation’s annual goals and objectives?

16. How do you concretely know when you are not taking enough risk; i.e. you may have a high risk appetite. It is easier to understand when we are outside appetite than when we are too timid.

Roles, responsibilities and engagement

17. Which team should take charge of risk appetite, strategy and planning or the risk management team? What are the pros and cons of each option?

18. What are practical ways of incorporating risk appetite analysis into a standard section for each board paper so that risk appetite decision making becomes more transparent, and the board is clear on what appetite the management are taking. How does this align / differ from a normal risk assessment (i.e. likelihood / impact) analysis?

19. How do we approach initial risk appetite discussions with the board?

20. How do you address leaders who think having risk appetite is adding more paperwork?

Aggregation/cascading of risk appetite

Is there a recommended method for linking BU risks or even system risks and risk appetites with the enterprise risk appetites?

When getting down to this granularity, this is often better achieved with risk metrics that may be cascaded down, rather than qualitative assessments. Depending on the approach, those metrics can be aggregated into composite metrics and escalated.

At Protecht we use risk taxonomies and libraries that can be used as the basis for aggregation, which can then be compared against an enterprise level risk appetite. This enables for the use of risk appetite at the enterprise level, where the risk applies to multiple departments or areas that are measured or managed independently.

Is it common to have different risk appetite for different areas, such as cyber security, AI, data privacy? How can we ensure it is aligned to organisation wide risk appetite?

Often risk appetite is aligned with a high-level risk taxonomy, such as you describe. This is or should be the expression of the organisation wide risk appetite. It sets organisation-wide boundaries in these areas that everyone should be abiding by or contributing towards in pursuit of objectives.

Where an organisation might have 3 levels in a risk taxonomy, how do you demonstrate cascading down and across it? Is appetite only set at top 1 or 2 levels, with KRI’s at lower levels? Should each level of a taxonomy be assessed against risk appetite?

If we referring to qualitative risk appetite, it’s often done at Level 1 only. However, I have seen instances where the organisational risk appetite was mapped against each division. Most had the same enterprise-level qualitative classification as a default but were adjusted if required. For example, an innovation division had a higher appetite for risks that could result in noncompliance than the rest of the organisation.

Cascading down more commonly occurs when appetite is expressed as metrics with thresholds, rather than for specific taxonomies. The same metric might be cascaded down to lower levels (such as the customer complaint example in the webinar). Another approach is a high-level metric that is broken down into more discrete metrics that influence or are associated with the higher-level metric.

Back to topRisk appetite implementation

Would you be able to provide examples of risk appetite articulation for risk culture?

This can become abstract and circular. A good risk culture would include your people living the values and boundaries set out by your risk appetite. You could set a risk appetite for risk culture, but typical qualitative labels don’t make sense to me. Would anyone ever set a high risk appetite for “allowing a poor risk culture”? That said, culture and/or conduct are often risk categories in risk taxonomies. In this case, qualitative statements that explain how good risk culture will be supported can form part of that risk appetite statement.

I think you should set a desired risk culture (and culture more generally) and measure that culture. That might include putting targets and thresholds when action needs to be taken, which is closer to risk appetite articulation.

How do we make risk appetite that can be applicable for both the operational and strategic risks? Do we define appetite based on the risk drivers/ criterion?

It may depend on the implementation, but particularly when applied to risk categories or domains, this can already be applied to both strategic and operational risk. If we take cyber as an example, you might set your risk appetite supported by metrics or a tolerance curve. This allows you to track operational risk against it. As cyber threats evolve, you may need to adapt your controls within existing operations.

Similar to the examples we used in the webinar, you might also forecast what the risk profile will look like when faced with strategic decisions. You can forecast ahead as to whether the organisation would still be remaining within its risk appetite if the decision is pursued.

What are your thoughts on using an enterprise risk matrix to drive appetite (e.g. for personnel safety, must rate low, for finance must rate moderate or less)?

This is an application of risk appetite, and I have used this approach before in an organisation that did not have a formal risk appetite statement:

- Certain risk categories had a target level, which differed by category

- Individual risks were aligned to a primary category

- Risks required formal action (treatment) if they were outside of their categories target level

When setting KRIs and their tolerances, should you look to include the upside of the ‘traditional target’ and set equivalent ‘green to amber’ and ‘amber to red’ tolerances to have oversight of overperformance?

I can interpret this question three ways; metrics applied directly to performance, KRI’s with double-sided boundaries, or stretch goals.

First, metrics can be applied directly to performance. KPI’s are measures of our objectives (or the variation around targets). The typical green / amber / red zones and associated thresholds can apply here. Conceptually the more appetite you have for variation, the further away the green and red zones are from each other.

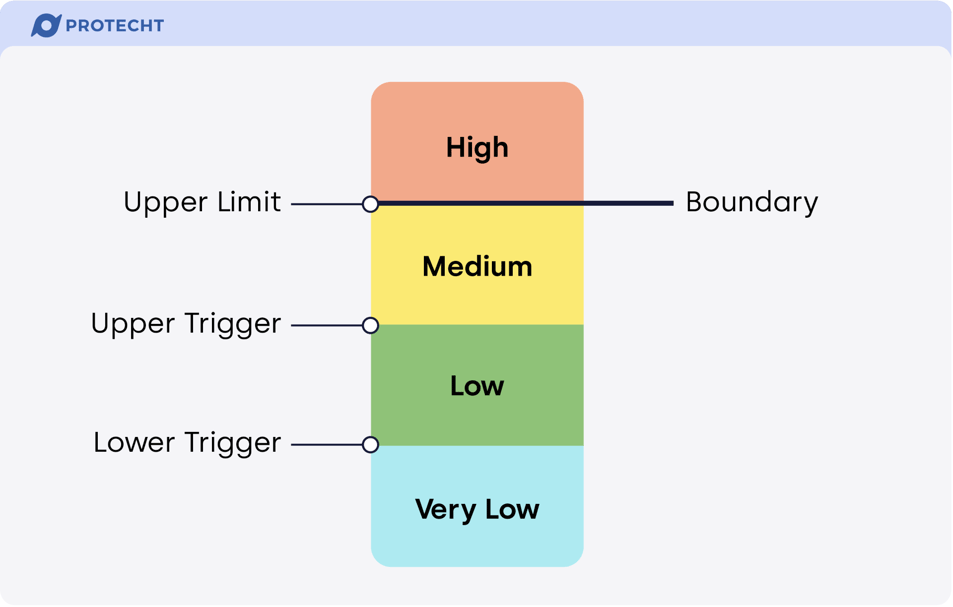

Second, KRI’s could have double-sided boundaries (least likely interpretation). This is usually to show we are taking too little risk, or there is a ‘central zone’ for ratios or similar metrics we should be sticking to.

Finally, you might have ‘stretch’ zones for overperformance. This typically only applies to KPI’s or performance. You might have a target zone that is green, with exceptional performance in other zones or colours. A practical application here is if you are overperforming in one area but falling short in others, this may warrant some resource optimisation to balance them out.

Any tips on how to quantify the chance of loss?

Related question:

- How should organisations adapt risk appetite models using quantitative method for emerging risks where historical data is limited, such as AI, OT cyber risk, or cloud concentration?

That’s a whole topic on itself, but here are a few quick tips:

- Use internal incident data if you have it. You don’t need as much data as you think, especially for risks that are more common

- Use external sources or industry sources if you have them. These may have frequency of risk events or ranges of losses. These can be a baseline (look for bias if your current assessments are much lower)

- Use subject matter experts to assess the range of potential likelihoods. If you are starting from a qualitative approach such as risk matrices, this is roughly what you are doing by asking them to select a likelihood category, they just get to be more accurate about the range.

For topics that are emerging or evolving, or there is higher uncertainty, developing ‘what-if’ scenarios can help clarify the potential impacts.

What is the interplay between the residual risk rating which is measured based on consequence and likelihood and a difference scale to the board appetite rating of very low to high?

In many frameworks risk ratings are calculated as you describe, by considering likelihood and consequence. If applying a risk matrix, that is usually converted into a single ‘level of risk’ with qualitative labels (you’ve used very low to high).

The board appetite is usually set just using those single level of risk, they aren’t set based on specific combinations of likelihood and consequence. This works in theory, though the board may not be clear on what combinations of likelihood and consequence constitute which risk levels. This is why it is good to ‘road test’ risk appetite and related processes to see if it actually meets expectations of key stakeholders.

Do you see risk appetite evolving toward dynamic, data-driven models rather than static annual statements? What does that look like in practice?

Great question (this made me re-think my reasoning on the topic while answering!)

Let’s start in reverse. Risk assessments are usually conducted (perhaps informed by data-driven models and therefore may be updated regularly), and then those assessments are compared against risk appetite. But could that data also be used to inform the setting or updating of risk appetite itself?

I’m reminded of optimisation techniques used in other domains:

- Define a value measure or reward function

- Consider any constraints

- Run simulations or machine learning models to define what provides the best chance of maximising the reward while within the constraints

The analogy with risk appetite is the concept of constraints, or the boundaries. I could see a future where a digital twin of the organisation forecasts a range of potential futures based on changes to risk appetite. Autonomous AI agents could then provide insight into which changes or combination of changes to risk appetite (presumably measured in objective metrics and thresholds) might increase likelihood of achieving objectives, and clearly show what the trade-offs are.

Getting to the practical component, if such a system were to be put in place, I think the onus is still on the board or governing body to agree to change those boundaries. It might just happen more frequently as environments change rapidly.

Should there be separate risk appetites for objectives and strategy?

We typically break objectives into strategic objectives (changing the organisation) and operational objectives (running the organisation). I’m inferring from the question that you or your organisation express objectives as more specific goals or actions that sit underneath broader strategy.

If that’s the case, aligned with the mantra of the webinar the broad answer is ‘if it’s useful’. If the strategies are quite broad it may be difficult to set boundaries around it, and the underlying objectives may be where acceptable variation in achieving them can be better articulated.

Compliance and risk appetite

If compliance risk appetite is zero, should the number of compliance breaches be set at zero? If yes, is this realistic?

Related questions:

- What about a health service that has no appetite for an adverse outcome leading to death?

- Compliance risks are typically articulated as ‘no acceptable risk’ but we have humans and this isn't the reality in practice. Any suggestions for application of appetite in a compliance risk assessment?

We see ‘zero’ risk appetite most often used in compliance or safety contexts. What this usually means in practice is:

- Big focus on prevention but an acknowledgement that these events still remain possible

- No acceptance of any intentional actions that could cause a breach (e.g. proceeding with launching a product known to have noncompliance issues)

- Every instance or near miss requires root cause analysis to identify potential improvements.

It can’t mean ‘we won’t expose our organisation to this risk’ because that is impossible. This is good one to test with scenarios on how it would be used in practice.

Definitions

What is the difference between risk appetite and risk tolerance?

Related question:

- 'Risk tolerance' and 'risk capacity' seem to be less popular concepts in frameworks now.

Risk capacity can have specific meanings in some sectors or risk types, particularly financial risk. Otherwise, I don’t see much practical use in capacity.

Definitions do differ, but we typically consider risk appetite to be a broader concept, sometimes used to describe a qualitative assessment. Risk tolerance related to metrics is more objective and quantifiable, and sets a specific boundary so you know when it has been breached. It is a specific implementation of risk appetite.

Decision-making, strategy and risk appetite

Should the decision to proceed with an opportunity be decided by the existing risk appetite? Or should the risk appetite be made flexible by the opportunities decided by the business/ management?

They should be considered together. Business or operational contexts change, such that opportunities that weren’t available or conceivable may now be available, but only if we are willing to take on risks we considered out of bounds. This prompts a more formal conversation on changing risk appetite; “are we ok taking on this extra risk in order to pursue this reward?”

This needs to be deliberate of course. If we keep shifting the boundaries every time a new opportunity comes along, then we don’t really have a defined appetite.

Should risk appetite be revised every year in line with the organisation’s annual goals and objectives?

They should go hand in hand. Accepting more risk can lead to the ability to pursue more lucrative objectives. While annual is a typical cadence, they should also be considered dynamically when applicable.

How do you concretely know when you are not taking enough risk; i.e. you may have a high risk appetite. It is easier to understand when we are outside appetite than when we are too timid.

Let’s cover two ways you might be able to address this.

Firstly, if you report objectives or performance together with risk appetite reporting or risk metrics, this might give you a signal. If you are underperforming but all of your risk metrics are well within the ‘green zone’ or all risks are well within appetite (assuming risk assessments can be compared against risk appetite categories), that can be an indicator that the organisation is being too cautious. This can result in more aggressively pursuing objectives or performance.

Secondly, you can add another zone if using metrics, with an example below from our Risk Appetite Statements and Frameworks Academy course. You can add a fourth zone (arbitrarily teal in this case) with a new threshold. This basically says “If we are in this zone, make sure it is only because we can’t get more reward by pushing towards the green zone”.

Roles, responsibilities and engagement

Which team should take charge of risk appetite, strategy and planning or the risk management team? What are the pros and cons of each option?

I assume you mean responsible for leading risk appetite development. Ultimately the board or governing body should approve the risk appetite (what risks management are allowed to take as part of their delegation), but in practice preparation often falls to the Executive team to then deliberate with the board. The actual logistics may be handled by the teams you mention.

If both teams exist, there is likely to be overlap in preparing risk appetite, but let’s take a look at each.

Risk team

- May have more knowledge about articulating risk appetite and risk measures

- May have better knowledge of how to link risk appetite statements and outputs to other risk processes and artefacts.

Strategy & planning

- Have better context of existing and potential strategies when considering risk appetite (what opportunities might we forego)

- If they are in charge of scenario planning (mapping potential futures), outputs can be used to inform risk appetite setting

- May be best at considering multiple strategies compared against different risk appetites. E.g. “We can do X within current risk appetite. We can pursue this higher reward strategy, but we need to formally change our risk appetite to match”.

In practice, it is often led by risk teams, but I’d love to see more strategy and planning teams own it. They are more invested in making it integrated into strategy. It also doesn’t make sense to set your strategy, then figure out the risks and whether they are within appetite. Treating both as iterative and integrated processes makes more sense when it comes to strategy-setting, regardless of who is involved.

What are practical ways of incorporating risk appetite analysis into a standard section for each board paper so that risk appetite decision making becomes more transparent, and the board is clear on what appetite the management are taking. How does this align / differ from a normal risk assessment (i.e. likelihood / impact) analysis?

Balanced scorecards or similar approaches can combine these. The most integrated approach are KPI’s sitting alongside KRI’s, which compares performance alongside tracking against risk appetite.

For decisions that are being put to the board, risk information can be incorporated into the information related to that decision. This can include a risk assessment itself (the level of risk associated with the decision), and how this might compare with risk appetite.

I work at a technology company with 1800 employees, and we are maturing our risk management framework. Risk appetite is currently not documented, it’s implicit. We are currently undertaking an exercise where we are working with each executive to identify the top risks in their area. The next natural step is to commence risk appetite discussions together with the Board. How would you suggest we approach this?

It may already be part of your discussions, but as well as identifying top risks in their area, consider asking how they know what boundaries they are allowed to push. This might help identify where boundaries are unclear, or there is no shared vision of what they are.

The next step with the Board may depend on their existing knowledge, but a few key steps:

- Educate board on risk appetite and how it is or can be used by both the board and the executive team.

- Define the objectives and risks that appetite need to be set for. Come ready with guidance; you should have business strategy/plan and you may have a risk taxonomy or classification system

- Consider walking through scenarios you think may push their appetite. (Or, if you are starting with something that the Executive team propose, walk through breaches to check their responses). This will help you determine their appetite

- Explain how tracking against risk appetite will be reported back to the board.

How do you address leaders who think having risk appetite is adding more paperwork for things that are already managed within risk limits?

First, check if they are right! Those risk limits are ultimately expressions of risk appetite and should probably be linked in some manner. Check how those leaders are (or could be) using the risk appetite statement. There may be a gap in how actionable it actually us, or they may simply be unaware of how it supports them in decision making.

Conclusions and next steps for your organisation

The breadth of questions in this Q&A highlights how central risk appetite has become, not as a static statement, but as a practical tool for decision-making, reporting and board oversight. From cascading appetite through the organisation, to using metrics and KRIs, to handling ‘zero appetite’ areas like compliance and safety, the common theme is the same: clarity comes from integration, not documentation.

If you want to see how these concepts come together in practice and learn how risk appetite can be translated into thresholds, embedded into reporting, and used to signal when boundaries are being tested, we encourage you to watch the webinar on demand.

Watch Risk appetite in action on demand and see what effective risk appetite looks like in practice: