Protecht held a webinar on Controls Design and Assurance earlier this month. The attendees completed several polls and asked a range of questions, some which we were able to answer during the webinar and others not. This blog contains a summary of all the poll results, plus the questions asked in the webinar and our responses.

Watch the recorded webinar on demand

Controls Design and Assurance webinar poll results

We polled event attendees across the three regions in which the webinar was held and aggregated this into global data. We asked two key questions about their current controls situation.

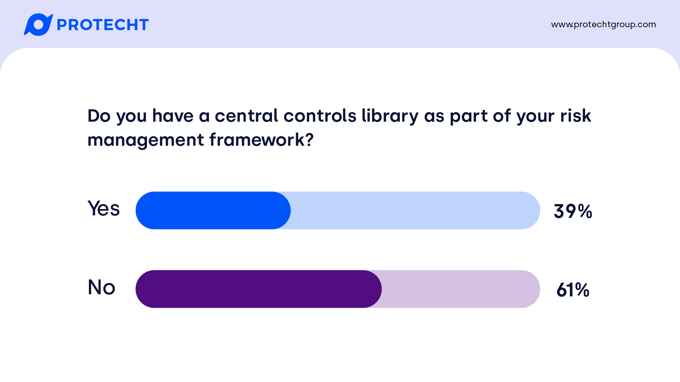

Do you have a central controls library as part of your risk management framework?

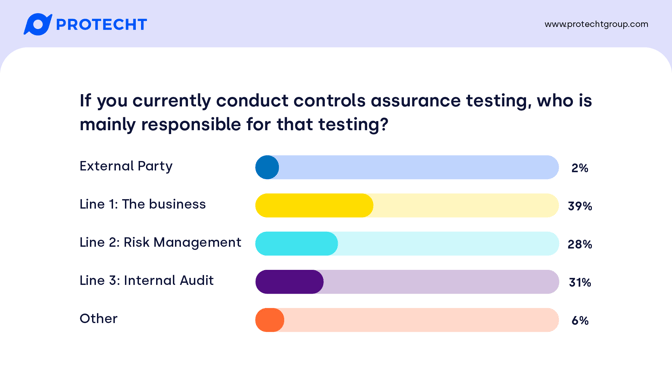

If you currently conduct controls assurance testing, who is responsible for that testing?

Controls Design and Assurance questions and answers

Do you have a central controls library as part of your risk management framework?

If you currently conduct controls assurance testing, who is mainly responsible for that testing?

What do you recommend to help define a key control from a non-key control?

What is the difference between control attestation vs assessment vs assurance?

Is there a threshold or guidance for when a particular control that may not fit into the control library categories, should be added into the library? What should be the questions we should be asking to make that assessment?

So what’s the best way to identify control gaps in your experience (apart from incident analysis)?

Do you recommend setting a tolerance for effectiveness of controls? It may be implausible to have the control 100% effective. For example using mail blocking as an example, you don't expect it to block everything but you want it to block most.

It's always worth critically assessing controls holistically and remove control layers that are not well designed/effective. More is not always better. Its also a quick win method for winning hearts and minds in the business as the they visually see you making their processes more efficient and valuable.

In your opinion what is the % of key control that you are expecting to see (compare to total amount control)?

Shouldn't the testing of controls be on all the identified key controls not just a sample of the key controls? Please clarify.

How does controls trend analysis work in a constant change environment impacting controls assessments?

Is it essential to have inherent risks on your risk register?

What is the difference between internal audit and controls assurance?

What is the best way of aggregating process level controls up to a risk profile (business unit) level to best look at high level residual risk?

What are your thoughts on control effectiveness definitions? Will they just be qualitative?

What advice do you have for cleaning up a controls library? Where is the best place to start?

Would you suggest categorising the types of control (e.g. key control etc.) to identify the ones to be captured and subject to testing/assurance?

What are some key control indicators? Can we say if a control reduces the risk from High to Low as a Key Control?

Hi there, great presentation. Likely that the businesses without a Controls Library could be smaller in size. What would a scaled down Controls Library look like?

Any thoughts on the assessment of compliance costs?

How can control indicators be utilized as a control assurance tool?

Do you have a central controls library as part of your risk management framework?

We see this as a measure of maturity. In terms of regions, those attending in the APAC region were a little ahead of the curve at about two thirds with a control library, compared to about half in EMEA and North America. Typically, we find that taxonomies and libraries for risks may exist without a library for controls – but rarely see this the other way around. Often early on in the risk maturity journey controls are free text and not aligned with a common taxonomy or library.

As organisations mature and their risk framework grows, we typically see a tipping point where there is recognition of duplication and an inability to aggregate or compare performance of controls in an effective or efficient manner.

If you currently conduct controls assurance testing, who is mainly responsible for that testing?

This is what we typically see, with some assurance activities pushed to Line 2. Protecht’s view is that Line 1 is responsible for operating the controls – and therefore should provide assurance that they are working effectively. We see regulators, particularly in the financial services space, pushing for more accountability in Line 1 for the effective management of risk and internal control, with Line 2 providing challenge and being an advisor – not performing control testing on their behalf.

While the numbers were reasonably close across regions, APAC had a lower proportion of Line 3 being the primary control assurance testers, with higher numbers in Line 1 and Line 2. Where internal audit is conducting the majority of control assurance testing, we see this as a stop-gap measure as organisations develop internal capability to conduct control testing directly in Line 1.

In relation to this methodology, how much of this process do you think sits comfortably with second line and how much in first line? E.g. should rating the effectiveness and testing sit with first line or does testing sit with second line?

Our view is that this should be a Line 1 function. Line 1 own the objectives, and therefore own the controls required to manage risks that affect achievement of those objectives.

In practice – and as highlighted in our polls – this may not currently be common practice, with some assurance pushed to Line 2. If there is a culture of Line being responsible for control testing, it may reduce the accountability of Line 1 to ensure that their controls are working effectively.

What do you recommend to help define a key control from a non-key control?

A basic litmus test is to ask ‘Is this control not negotiable? Or important but negotiable?’ For example, most of us would probably not want to drive a car without brakes, but might drive if our rear windscreen wiper wasn't working.

In a business context, we would probably not want to run our computer at all if password management was missing or rendered inoperable, but we might be willing to accept a 2-factor authentication tool to be ineffective or missing for a period of time from a system that stores non-sensitive information.

What is the difference between control attestation vs assessment vs assurance?

Great question! Let’s cover each of them in turn.

Control attestation - At a minimum, a control attestation is a recorded and auditable statement (such as in an enterprise risk management system) that a control is effective (or not), usually made by the control owner or operator. Often this is based on an assessment of its operation, but may also be its design. It may be ‘reasonable opinion’ only, but may be further enhanced with specific evidence of the control attached to the attestation.

Control assurance – This is gaining assurance that an individual control is achieving its intended objective. This is achieved by testing the control is designed and / or operating as expected. There are multiple types of control tests.

Controls assessment – As we covered in the webinar, controls assessment considers a collection of controls, and whether they manage the risk as a whole. This can help identify potential gaps – you can’t test something you didn’t know you needed!

A rule across all of these is to test or assess controls, not data. Looking at historical data might tell you whether the risk has occurred or not – but may not tell you whether you expect your control to perform in the future. It’s like leaving your car unlocked and saying that because it wasn’t stolen, you must be managing the risk of theft well!

What are the most appropriate control categories to use when creating a control library from scratch?

If we assume you mean control taxonomies, Protecht has a comprehensive control library available within its Protecht.ERM system, which can then be adapted to customer needs where required.

There is no one correct approach, however we consider the characteristics of controls and group them in this manner, aiming for a ‘mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive’ outcome. Here are a few example of high level control categories: people management controls, physical controls, segregation of duties, authorisations and approvals, Verification, and monitoring and review.

You might consider defining control categories based on the type or types of risk they control. In our experience this can lead to duplication, as similar controls can control different types of risks.

Do you recommend a controls rating table for design effectiveness and operating effectiveness and an overall rating depending on the ratings for design and operating effectiveness?

While Protecht doesn’t recommend a specific method, we find that this is a very common approach. Other alternatives include a simple Effective / Ineffective rating if either Design or Operating effectiveness is not considered to be fully effective.

We do recommend that generally design effectiveness is considered of higher importance. If something is not designed to address the risk or causes adequately, it doesn’t matter whether it is operating or not.

Is there a threshold or guidance for when a particular control that may not fit into the control library categories, should be added into the library? What should be the questions we should be asking to make that assessment?

There is no simple answer, and will depend on how your existing categories are structured. A few questions that can help:

- Is it similar in performance or characteristics to other controls within a category? Should we expand the definition of that category?

- Do we foresee other controls with similar characteristics to this one being used in the future? Can we create a category that would fit this control as well as others we might implement in future?

- If we create a new category, would we still agree with how we’ve categorised it if the control was applied this control to other types of risks?

So what’s the best way to identify control gaps in your experience (apart from incident analysis)?

We think the best way is to integrate risk bow ties in risk and control self-assessments or risk workshops. The purpose is to be curious and identify as many potential pathways for how risks might occur. This can really help identify causal or impact pathways where control gaps exist.

Do you recommend setting a tolerance for effectiveness of controls? It may be implausible to have the control 100% effective. For example using mail blocking as an example, you don't expect it to block everything but you want it to block most.

Generally yes – but of course it depends on what the metric is measuring and how the control modifies risk. You need to decide what you will accept for the metric chosen, and at what point you may need to address the effectiveness of the control. Setting tolerances and measuring Key Control Indicators are also great for identifying trends. In the example you’ve provided, you might see a negative trend in the performance of your email blocker, even before it reaches your defined threshold, which might allow you to act early to review and improve its performance.

It's always worth critically assessing controls holistically and remove control layers that are not well designed/effective. More is not always better. Its also a quick win method for winning hearts and minds in the business as the they visually see you making their processes more efficient and valuable.

We couldn’t agree more! Sometimes there is an inclination – particularly in response to incidents – to add more controls. A benefit of the bow tie method and looking at causal pathways is optimising investment in controls. This might be removing a non-key control from an overcontrolled causal pathway, and re-allocating those resources to another causal pathway that has no or few controls.

What should be a good frequency for control testing? You mentioned periodically but could you be more specific?

There is no perfect answer, and each control may require a different frequency depending on the nature of associated risks and how the control modifies risks, specific to your organisation. You might have some that are monthly (or less) and others annually. These are some general rules to follow in setting the frequency of testing, all other things being equal:

- Risks that have a high impact if they occur should have their controls tested more frequently

- Controls that give off no other evidence of their performance (such as Key Control Indicators) should be tested more frequently than those that don't

- The effort required to test the control can also be a factor in whether there is a return on investment in testing it

- How quickly the risk might occur if the control was not working

- The testing frequency of other controls over the risk

This assumes that control testing is being performed by the First Line. For key controls that may have higher frequency of testing, this may be supplemented by less frequent challenge from the Second Line and Third Line.

In your opinion what is the % of key control that you are expecting to see (compare to total amount control)?

We often recommend the Pareto rule or 80-20 rule, but always with caution. You should evaluate your key controls based on whether they are ‘non-negotiable’. I.e. You wouldn’t conduct the activity without the control, or would take immediate action to rectify a weakness.

Inclusion of controls in your formal control framework – whether key or non-key – should be on the basis that it provides sufficient assurance that you will achieve your objectives in a cost-effective manner. If you identify 20 key controls, we would not suggest finding 80 additional non-key controls just to fit this rule!

Do you find that there is a lot of re-using of controls across business units in a large organisation?

This is often related to maturity of both risk frameworks and systems solutions. In early maturity, organisations may have siloed approaches without any standard taxonomies or libraries. They may document controls that are nearly identical being applied in multiple areas, but may be named differently and are not able to be aggregated.

As organisations mature, they develop standardised control libraries that can be applied across the organisation. This has a range of benefits, but in particular it allows for reporting at an aggregated level that can provide comparison of control effectiveness across business units. It also means that if a business unit identifies a control gap, they might be able to leverage what other business units have already learned.

Shouldn't the testing of controls be on all the identified key controls not just a sample of the key controls? Please clarify.

In an ideal world yes, all key controls should be tested. This can come down to maturity, and whether Line 2 are performing control testing that should be the responsibility of Line 1.

How does controls trend analysis work in a constant change environment impacting controls assessments?

This question highlights why 'set and forget' risk management is not effective, and needs to be integrated into decision making and change management processes. While Risk and Control Self-Assessments may be conducted on a cyclical basis, risk profiles (and risk bow ties if you use them) should also be updated as business environments and processes change.

This works both ways; while you might find new controls that need to be implemented or existing ones to modify, you might also find controls that are no longer efficient or no longer address the risk.

Focusing on the trend analysis part of the question, constantly changing controls may limit the ability to report some information, such as how an individual control has performed over time. However if controls are aligned to a taxonomy, it can still be aggregated at this level to provide insight into the overall performance of that type of control over time. You will also be able to report on the effectiveness of characteristics that are common to all controls, such as design and operating effectiveness.

If you have a specific example or use case, we'd love to hear more.

I agree that policy and general training are not controls. Where would you include a check to confirm the fundamentals are actually happening though? In operational compliance? Would you just add a question to confirm these things fundamentals are in place and up to date? Or a KRI?

We generally recommend considering policies and procedures when assessing the design effectiveness of controls. These documents often include controls or descriptions of controls within them, rather than being a control in and of themselves. They usually include responsibilities, clarity on when controls should be applied, and how they are intended to operate.

They can perform part of your compliance attestation framework as to whether the policy or procedure is up to date, and whether it has been distributed or trained upon. As you highlight, some of these can be expressed as metrics, such as Key Risk Indicators.

Is it essential to have inherent risks on your risk register?

The biggest benefit is that the difference between inherent and residual risk highlights the effect that your set of controls have on the risk.

It can be difficult to know which controls have the most effect (and which ones are key) if you don’t consider these differences.

What is the difference between internal audit and controls assurance?

Internal audit is the Line 3 function that provides assurance over whether Line 1 (the business) and Line 2 (support functions such as risk and compliance) are effectively managing the risks to the organisation’s objectives. Controls assurance is the activity of testing whether controls are designed and operating effectively.

While controls assurance should be conducted by Line 1, Internal Audit (or Line 3) should be verifying that Line 1 are providing that assurance, and that Line 2 are challenging that assurance where necessary. Risk teams and internal audit may also perform controls assurance independently – however performance of controls remain the responsibility of Line 1. Internal audit may also provide an assessment of the adequacy of the risk framework.

What is the best way of aggregating process level controls up to a risk profile (business unit) level to best look at high level residual risk?

We call this ‘Risk In Motion’ at Protecht, where we can look at the aggregate of risks and controls of a business unit and how they are assessed. If you also document more detailed process level risks, the same concept can be applied, allowing you to scale up or down the detail of your reporting depending on the audience.

What are your thoughts on control effectiveness definitions? Will they just be qualitative?

We generally find these are qualitative. For example, Design Effectiveness may be defined as 3 levels:

- The controls design fully meets the control objective(s)

- The controls design partially meets the control objective(s)

- The controls design does not meet the control objective(s)

We recommend that a controls assurance framework includes additional detail on what factors need to be considered when assessing design and operation. For design this might include whether the control objective is documented, whether it is clear who owns and operates the control, how it is intended to operate etc. Some of our customers standardize this approach and apply formulas to provide an overall assessment of effectiveness. If you apply a formula, we recommend performing a sense check to ensure it feels appropriate.

Compared to design effectiveness, operating effectiveness is more flexible in having metrics applied that can support an assessment of its effectiveness rating.

What advice do you have for cleaning up a controls library? Where is the best place to start?

If you haven’t already done so, the first place to start is engaging your stakeholders in the benefits. This can include:

- Standardisation of controls across the organisation, which can increase efficiency (i.e. find out who is doing it best, and duplicate it)

- Consistent language for controls, improving the ability for people to discuss and act on them

- Consolidation of controls that might currently be applied in different areas – perhaps they can be applied at a higher level across the entire organisation, rather than in silos

On the practical implementation side, if you don’t already have one the best place to start is developing a taxonomy for your controls. Then you can review all of the controls across your organisation and align them with your taxonomy. This might help you find items documented as controls that are not controls, helping with the clean-up.

Once you’ve aligned all of them, you can start reviewing each category in your taxonomy, and grouping together similar looking controls. From there, you should be able to make recommendations for which control names can be consolidated.

Would you suggest categorising the types of control (e.g. key control etc.) to identify the ones to be captured and subject to testing/assurance?

We do recommend categorising key vs. non-key or negotiable controls. Key controls are those that should be subject to more frequent or rigorous testing, while the non-key are those where control testing should still be conducted, but perhaps less frequently and with less scrutiny from Line 2 and Line 3.

What are some key control indicators? Can we say if a control reduces the risk from High to Low as a Key Control?

If there is a single control that reduces a risk from High down to Low, the answer is probably yes! Usually the answer is not so clear cut, as often it is a collection of controls that affect the overall rating of a risk, rather than a single control. When using qualitative scales, isolating an individual control might not result in a shift in a risk rating but still be an important control. That’s why it is important to understand the causal pathways and whether a control is considered non-negotiable.

There are no key control indicators that are universal, as they need to be applied to the individual control and how it is expected to operate. This usually comes down to asking questions about what evidence would the control give off if it was operating well (or not). Using an example from a previous question, the percentage of spam emails that get through your filter and reach your staff provides an indication of how well it is operating.

Hi there, great presentation. Likely that the businesses without a Controls Library could be smaller in size. What would a scaled down Controls Library look like?

If you don’t have a controls library and are looking to implement one, you might benefit from partnering with one department or area you work well with in order to embed it. Focus on those controls that are key, and show the benefit of obtaining assurance from some of your key stakeholders.

While we are strong advocates of a taxonomy, for small libraries you may not include one at the outset, or your taxonomy might only have a single level.

How can you effectively communicate the difference between effective controls and what people think are controls but are in fact a described process?

This can be an interesting one to tackle. Having clear definitions of causes, risks, impacts and of course controls, can help alleviate some of the confusion. A control is a measure or action that is taken to modify risk. The implication of your question is that they might be describing a process that is required to achieve a desired outcome – what we often call critical success factors or critical processes - but doesn’t modify risk related to that outcome. By asking them how the process modifies risk, it might help them reframe it.

In case you hadn’t noticed we love the risk bow tie method at Protecht. We find this often helps reinforce that failed critical processes are usually interim events between a risk event and impacts, and is not a control.

Any thoughts on the assessment of compliance costs?

I will assume this means the cost of complying with the testing program. The control testing and assurance program needs to be cost effective – if it costs more than the risks being managed if they were to occur, then clearly something is amiss! Whether qualitative or otherwise, I would suggest incorporating the testing of a control into the cost of the operating the control when assessing it return on investment when applied to the risk (how much it modifies the risk). As noted earlier, the cost of testing should be also considered when assessing the frequency.

If the question refers to regulatory compliance, you will of course need to assess the costs to meet those, based on the frequency and the estimated effort required for testing.

One control can be linked to a number of risks. When building your control library, how do you avoid the situation where you have a couple of hundred controls. How does protecht define risk events?

Absolutely, one control may be be linked to a number of risks. Manual risk management processes, such as having the control listed in multiple spreadsheets, can be an administrative burden or cause errors where one spreadsheet is updated after control testing and others are not.

Our Protecht.ER